那是我第三次带着巴莱斯特里(Balestrierius)乘飞机,从圣地亚哥飞往芝加哥。

巴莱斯特里是一只大提琴。就像最具盛名的斯特拉迪瓦里(Stradivarius)琴一样,意大利提琴都是以它的制作者的名字命名。巴莱斯特里的制作者托马斯•巴莱斯特里(Thomas Balestrieri)

是意大利曼图亚(Mantua)的制琴师,于1750 至1780年代活跃在意大利制琴界,他是意大利克雷莫纳(Cremona)制琴学派最后的一位大师,他一生制作了小提琴,中提琴二百多只,

大提琴近五十只,散落在世界各地。

我是怎样和提琴珍品拉上了关系?这要从女儿的学琴生渊说起。

女儿可以拉全尺寸大提琴时,我们给她定制了一只国产琴,作者是上海某琴行的王先生。王先生是上海音乐学院提琴制作专业毕业生,据说还是上音前副院长谭抒真的弟子,

谭抒真是中国当代德高望重的音乐教育家,小提琴家,乐器专家,中国提琴制作事业的开创者。王先生那时候开琴行搞得风生水起,我们认识的上音的老师也推荐到他那里买琴。

2500美元定了琴,三个月后取货,那是2001年。焦急的等待中盼到了琴,打开试拉,大失所望。那是一件平庸不过的,外形是大提琴的木工活,声音如未熟就掉地的青涩的苹果,

没有人会感觉它有水果味。

女儿的琴技在进步,演出比赛不断,着实使我们焦急。拉琴的人,如果没有一只好琴,在比赛中会吃大亏,这道理很简单。钢琴比赛,参赛人都使用同一部钢琴,最后比出来的是技艺。

提琴比赛,每人用自己的琴,琴发出声音的质量不光和技艺有关,裁判不会费心去把二者区分开。有些人为了比赛,去租一只好琴,当然不失为一个办法。但是租来的琴很难在短时间内掌握住,

对比赛的发挥十分不利。长期租,费用太大,好琴租一天可花费200 到500 美元。我们决定买一只好点的琴。

什么琴是好琴?初中时,好友借给我一只广州产的的百灵牌练习琴,是它使我对提琴有了认识,甚至对音乐发生了兴趣,终生受益。在我西南的故里,常见的好琴是上海的金钟琴和和珍珠琴,

外国琴不多。有一次,省歌舞团演出,有一个小提琴独奏。主持人介绍,那只独奏琴有一段特别的经历,那是西北王马步芳私人乐队中的一只琴,战争中被军队缴获,省文化局花了一万人民币买来,

在那个年代,这是一件非常昂贵的乐器。当时对那琴的音色并没有特殊的感觉,只知道那是一只德国琴。从此认为德国琴是最好的。

“意大利琴才是最好的。”女儿的大提琴老师对我说。

女儿的这位老师是圣地亚哥交响乐团的大提琴演奏员,住在拉荷亚(La Jolla)。

“这是一只意大利琴,”她打开琴盒,向我们展示她的琴,“价值二十五万美元。你们知道,我的这栋房子,七十年代购买时,也只花了二十五万美元。”拉荷亚是圣地亚哥的高档住宅区。

这位老师只是乐团的普通成员,而独奏演员对乐器的要求更高。乐团其他成员的情况也大致如此。比如另一位毕业不久的演奏员,贷款买了一只琴意大利,价值十七万美元。当然我也知道,

马友友的那只1733年的意大利琴蒙塔尼亚纳(Montagnana),价值近三百万美元。昂贵的职业,昂贵的爱好。

后来,当我对提琴品牌有比较客观的认识后,知道了,“好琴”对大多数人来说是一个相对的标准,决定于你的能力和用途。音色和易于拉奏是两个最为重要的指标,而能够达到这两个指标的琴,

可以来自任何国家和制造商。意大利十八,十九世纪的手工琴之所以有很高的声望,是因为它们能长期不断地完美满足这两个指标,以及其他指标。当然,市场是很清楚那些指标的代价,要求越高,

代价也越高。

我无意花很高的代价为女儿去买一只琴,一是经济能力的限制,二是不确定女儿的兴趣会发展到哪种程度,两万美元左右大概是我的价格范围。

“又要拉好琴,又不想多花钱,那就要辛苦你自己了。”一位懂琴的好友这样揶揄我。

所以,在看到eBay(网趣)上有一只1779年的意大利琴,售价7000美元,我当时的心情可想而知。那只琴的卖家在北加州的蒙特利(Monterey)。

我乘飞机到了风情万种的海湾城市蒙特利,又租车找到了地址。那是一座颇为豪华的海边住宅,接待我的是一位中年华裔妇女,不会说中文。她立即让我上她的车,

带我去另一个地方。车上她告诉我,琴是她父亲的。她的父亲刚去世不久,之前独居在一处公寓房,现在就去那里看琴。她还告诉我,父亲是原香港管弦乐团的大提琴手,

七十年代退休后来美国,和她们居住在一地。单人公寓虽已清理过,仍然散发出单身老男人那种特有的气味。房子的空间几乎被黑胶木唱片和书报堆满,一只大提琴平躺在书堆上,

没有弓,没有码,没有弦,像一个脱光了衣服的病人。

“这就是。父亲来美国后从没有拉过琴。琴盒,琴弓都送了人,只有这琴,他想留着作个纪念。”

这是一只饱经风霜的琴,木质陈旧,漆色仍光润清亮,面板有几处裂纹,琴颈重新接过。琴内商标老旧,但仍可读,意大利文印着制作者名字,Thomas Balesterieri,制作日期,1779。

除了制琴商标,琴内还有一张修琴标签。1899年,这只琴在爱丁堡(Edinburgh,England)的James Hardie & Sons琴行进行过维修,大概是修复琴颈。考验我的时候到了。

在这样一个无法试音的环境下,一只衰旧的琴,它的价值到底在哪里?我再一次环顾那小屋,昏暗中浮着霉味,墙上的镜框中,老人的英国圣玛丽音乐学校(St Mary’s Music School)

的毕业证书还没有被取下来,我感觉到,沉浸其中的那老音乐家的气息,不会是假的。我不相信他用了几十年的琴,会比不上那只上海青苹果,加上对意大利琴的莫名崇拜,我决定买这只琴。

我们以5000美元成交。

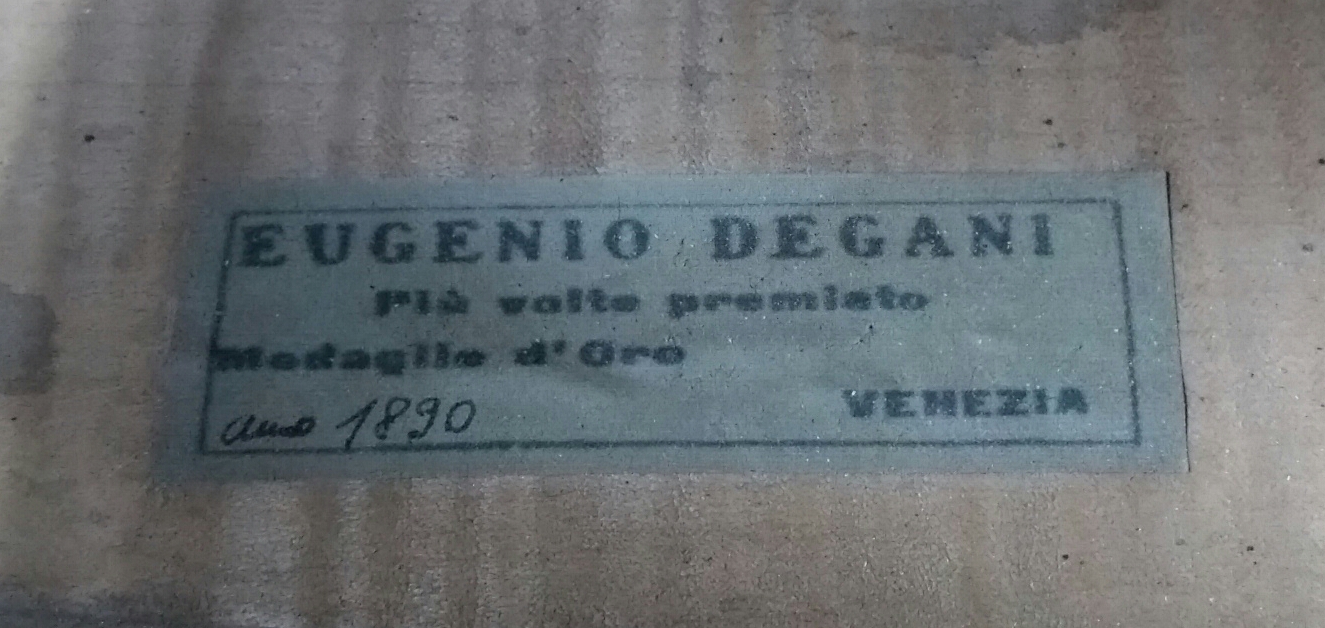

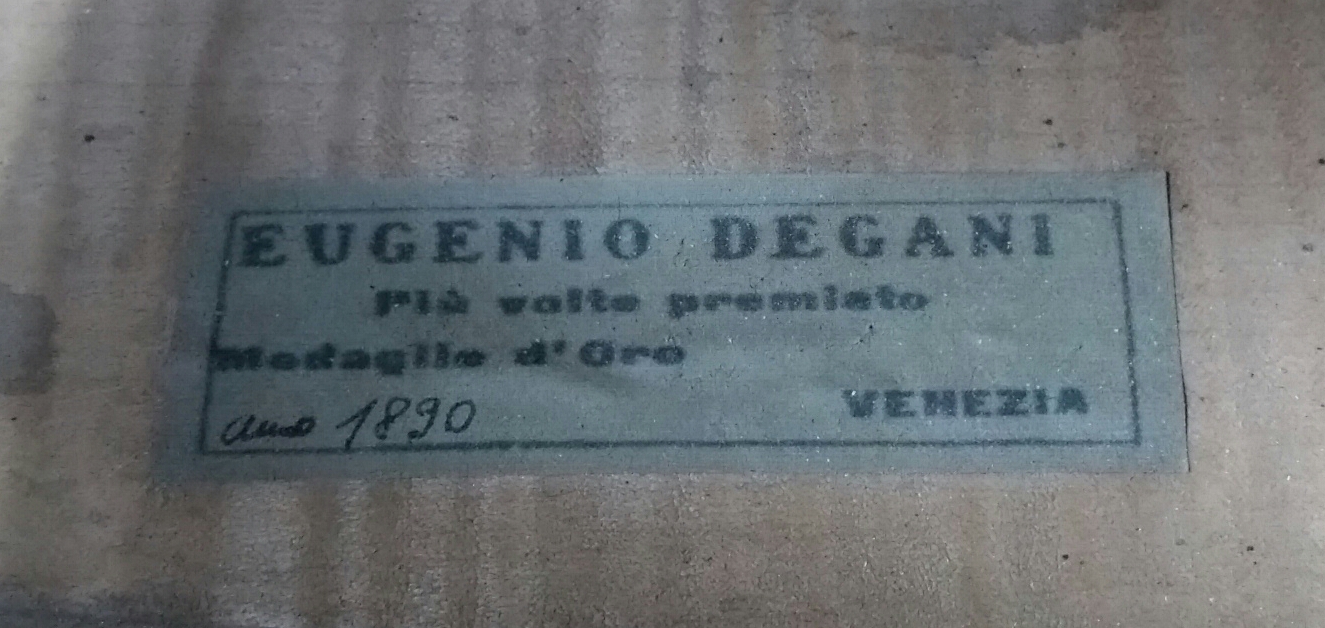

巴莱斯特里琴的商标

这样我便第一次带着巴莱斯特里乘了飞机。

一到家就立即装好琴码琴弦,开始试琴。不负所望,出来的是一只老琴的深沉内敛的声音,远远不是上海王先生的琴所能比。不足之处是声音响度略嫌不够,用于室内乐演出毫无问题,

在大剧场中演出可能声音不够响。不管怎样,我是相当满意,用了这只琴,女儿的演出和比赛大概会上一个台阶。

我开始研究这只琴的历史。网上资料显示,托马斯•巴莱斯特里制作的近五十只大提琴,已有二十几只被世界各琴行登记,拥有证书。拥有证书的巴莱斯特里大提琴,最高价值为约五十万美元,

最低的也近二十万美元。我于是有了为这只琴弄一份证书的念头。

洛杉矶罗伯特考尔琴行(Robert Cauer Violin)大概是南加州最具有权威的琴行之一,主人罗伯特.考尔有很深的专业资历和技艺,曾担任美国制琴家联合会主席。明白我的要求后,

考尔先生抱出一大扎参考资料,从地上堆起有一米多高,一本一本地翻看查阅。最后告诉我他的结论。

“我不能给你出这个证书,因为这样两个原因, 1. 这只琴琴头的卷花和巴莱斯特里制作的卷花的形式不一样。 2. 琴边的嵌线和巴莱斯特里制作的嵌线的材料不一样。”说着向我展示有关的图片和文件,

里面都详细记载巴莱斯特里制琴技术的特点和风格。我申辨,这只琴1899年修过琴颈,琴头可能因此换过。考尔先生说,这种可能性存在。但如果琴头换过,就很难把它定义为巴莱斯特里琴,

况且嵌线问题没有办法否定。我佩服考尔先生的敬业精神和专业知识,那天他和我折腾了三个多小时,只收了50美元。最后他告诉我,如果想进一步证实这琴的真伪,可以到意大利克雷莫纳的提琴学院,

那里有更全面更专业的技术。我知道,知名琴行为名琴出具证书是相当谨慎的,特别像考尔先生这样的人,不能在业界留任何瑕疵。

虽然没有得到证书,我还是愿意称这只琴为巴莱斯特里。琴头且不说他,难道托马斯•巴莱斯特里就不会使用其他材料的嵌线?当然,我也不打算到克雷莫纳去把这事彻底弄清。

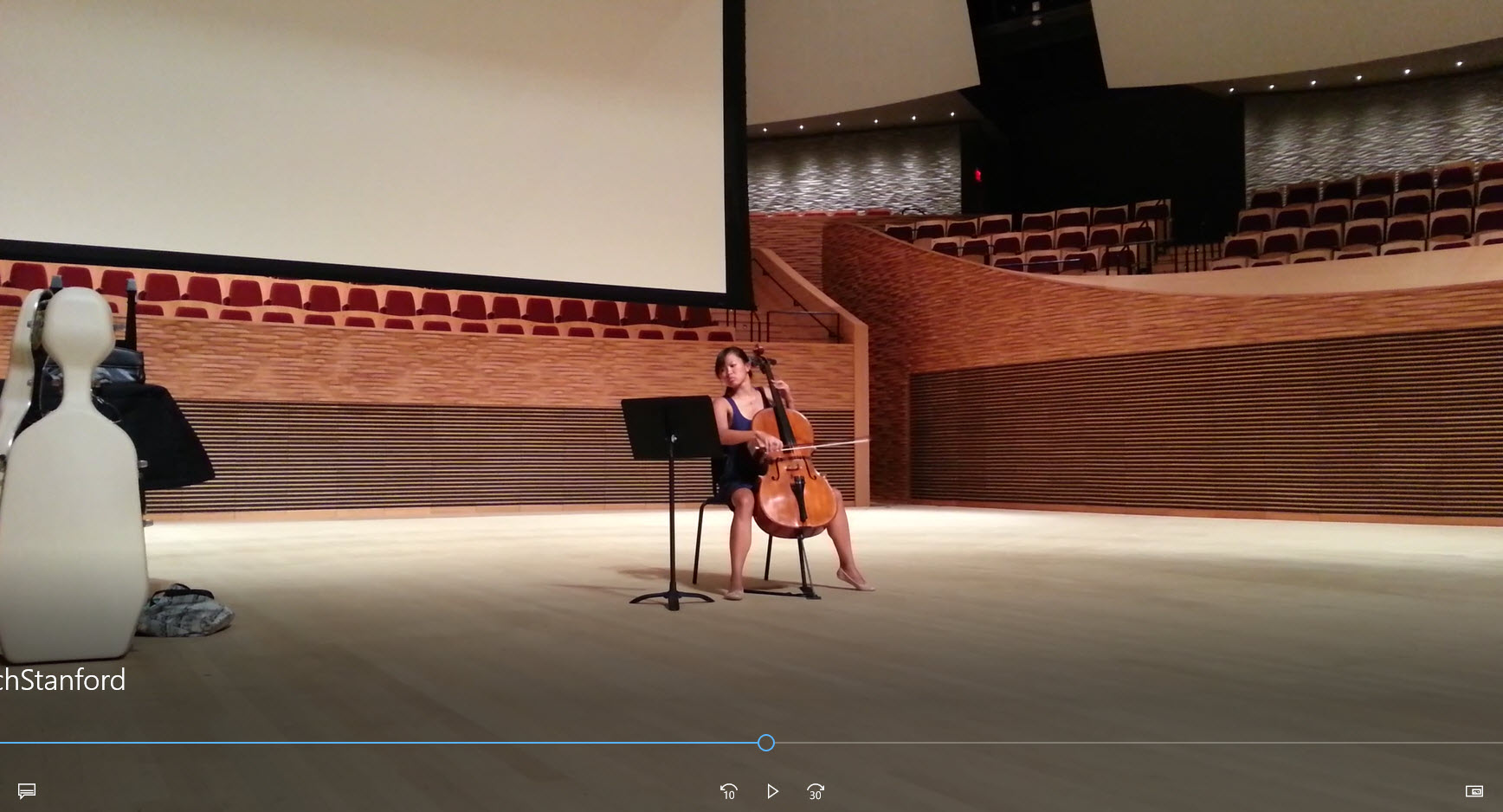

巴莱斯特里琴在教堂演奏

圣桑第一大提琴协奏曲

女儿用这只琴赢了不少比赛,使她在教堂,图书馆等小型场合作过多次演出,效果都相当不错。后来得到一个机会和圣地亚哥交响乐团在科普利音乐厅(Coply Symphony Hall, San Diego)表演,

终于可以检验巴莱斯特里在大剧场与大乐队合作的表现了。

那天拉的是圣桑(Saint-Saens)的第一大提琴协奏曲。演出中我坐在剧场靠后的座位上,因为有反射,那里的音响应该是很好的。结果是,只要乐队有较强的演奏出现,

大提琴的声音就被压住而很难听到,使一首协奏曲听得很不完整。正如我一开始就有的直觉,巴莱斯特里是一只室内乐的琴。我决定要再弄一只有更强音响,可以在大剧场和大乐队演奏的琴。

我第二次带着巴莱斯特里乘飞机,是到佛罗里达的奥南多去看一只琴。

那是奥南多的一位中学教师,因急需钱要出售他的一只法国琴。据他介绍,这只琴在大剧场演出过,效果不错,所附的图片也很顺眼。中学教师带着他的琴和女友到了旅馆的会议厅,

手里还提着一瓶红酒,说要为成交而庆贺。他是一位资深的演奏者,坐下来就用他的琴拉了巴赫的D大调组曲。我为之倾倒的时候,请求他用我带去的巴莱斯特里把同样的曲子再拉一遍。

二者效果基本相同,那不是我要的琴。尽管这样,我们三人还是喝了红酒,愉快告别。买琴时,带一只琴去作比较,是女儿的老师教给我的好方法。

现在第三次带着巴莱斯特里乘飞机,是因为芝加哥一位音乐学院学生有一只1890年的意大利琴要出售,巴莱斯特里仍是我的随行参谋。

这位学生原来主修大提琴,在意大利花了11000欧元买了这只琴,一年后决定改修指挥,所以要把琴卖掉。这只琴有相当正式的琴行出售发票,琴内意大利文的商标,

写着制作者是欧亨尼奥•德加尼 (Eugenio Degani),制作时间1890。欧亨尼奥•德加尼是现代威尼斯提琴学院的创始人,于1901年去世,他的琴在世上流传比较多,价钱在几万到几十万美元之间。

我现在已经不太很在意琴的正统身世,我要洪亮园润的音色,能在大音乐厅演出。这只琴的音量比巴莱斯特里要响一倍,音色要差一些,但我看得出其原因,琴码质量不够好,

没有用最好的弦,指板过低导致琴码太矮而影响弦的震动。我感觉,这些问题都可以通过我自己的努力解决。当场就以卖主的要价8000美元,买下了这只琴,加上一个质量不错的玻璃钢琴盒。

此时是晚上12点,距我的回程飞机还有5个多小时,于是我带着两只琴,在芝加哥机场大厅的长椅上,和无家可归的人们一道,睡了一晚。

德加尼琴的商标

回到家,急于向家人展示我的成果。忽然看见巴莱斯特里的琴盒头上有被撞过的痕迹,打开琴盒一看,惊吓和怒气从脊背冲上头顶,我的脑袋一下子炸了,巴莱斯特里的琴头整个从琴颈上断落,

像被钝刀砍头的人,只有几根筋连着头颅和身体,那是琴弦。我想痛哭,想叫喊出来。交付托运时,我把“易碎物品,小心轻放”的标签贴满了琴盒,想不到还有这样烂的航空服务。

又是有经验的大提琴老师告诉我,在对待你的琴上,想省钱是危险的。她旅行时,大提琴从不放货仓托运,要单独为它买一张机票。所幸,刚买的德加尼无恙。我想,我现在必须要成为提琴专家了,

否则我怎样应付这两只琴的保养和修复?

我在芝加哥的一所音乐学校注册了一门提琴制作与维修的网络课程。课程使用美国当代提琴制作家亨利•斯特劳贝尔(Henry Strobel)的一套教材,包括提琴的木工制作,上漆,调试,

维护的所有技术细节。作为理论学习的实践,我首先把巴莱斯特里的琴头修复了。成功的喜悦使我不知天高地厚地重新打造德加尼。我把指板拆下来,用红木垫高,把面板的漆全部去掉,

重新漆过,丢掉原来的琴码和琴弦,换上世上公认的最好的法国Despiau琴码,丹麦的Larsen和奥地利的Spirocore琴弦。后来知道,大概是因为运气,使我没有把事情搞砸。

就拿这样大面积漆琴来说,是十分危险的举动,很可能使琴的音色全失。我用的是有名的1704漆配方,这种漆配方据说创自1704年,是意大利斯特拉迪瓦里(Giacomo Stradivari)

家族的后代从家庭圣经中流出到社会上。

检验我的提琴技术学习结果的,是三个月后女儿参加的一次较重要的比赛。我和妻陪着女儿一道去,她用德加尼演奏德沃夏克(Antonin Dvorak)的第一大提琴协奏曲。比赛结束,

裁判握着女儿的手说,“拉得很不错,琴声音很好,演出服也漂亮!”我们三人都得到应属于自己的称赞,妻是专负责准备演出服装。

以后,女儿用德加尼在洛杉矶的托兰斯文化艺术中心(Torrance Cultural Arts Center)和圣地亚哥大学康拉德•普雷贝斯音乐中心(Conrad Prebys Music Center,UCSD)作过三场公演,

效果都不错。在圣地亚哥大学的两场演出后,有人对我说,他听不出这琴声和马友友的有多少差别。这种话的水分有多重,我自己明镜般地清楚,但作为一种鼓励和善意的认可还是使人很欣慰。

在圣地亚哥大学表演的是肖斯塔科维奇(Dmitri Shostakovich)的第一大提琴协奏曲。这是一首被音乐界公认难度很大的曲子,强烈的抗争情绪和纯净的悲切凄怆的对比,

被德加尼在音乐厅中释放得不算坏,受到指挥和观众的好评。

德加尼琴在圣地亚哥演奏

肖斯塔科维奇的第一大提琴协奏曲

女儿念大学后,有一次和在北加州的她通电话,她轻描淡写地说,周末有个演出。

“什么演出?”

“和学校交响乐团拉乐可可。”

“为什么不早告诉我们?我们要开车过来听!”

女儿在学校的音乐比赛中赢了,要和学校乐团演出柴可夫斯基(Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky)的大提琴协奏曲《乐可可主题变奏曲》。当我和妻坐在斯坦福音乐厅等待音乐会开场时,

距知道这个音乐会的消息不过20个小时。虽然协奏的乐队表现差强人意,女儿的发挥却相当不错。她手中的琴表现出了最好的状态,比在圣地亚哥时更佳。德加尼时而鸣唱柴可夫斯基那无与伦比的优美旋律,

时而又模拟激昂热烈的情绪,柔情和力量都能出得来,乐队压不住的琴声在大厅每个角落回荡。

音乐会后,我赞扬女儿,说:

“这大概是你表演水平的最高峰,也是你的琴的最好表现了!”

“难道我和我的琴以后就是下坡路?”她打趣地问我,接着说,“这个曲子我实在是太熟了,其实并不难。年纪大了,感觉更成熟一些。你说到琴的音色,大概是因为这音乐厅的效果特别好。”

我知道,她和她的琴在音乐会中有出色表现的真正的原因,是因为她大学一,二年级选修了音乐系的室内乐理论与实践的课程,花了不少的时间和德加尼在一起。按我的经验,这是不可持续的。

以后大量繁重的课程,学习及人生计划,会占去相当多的时间,那时候,兴趣和爱好自然就会往后面摆了。我没有说出口。

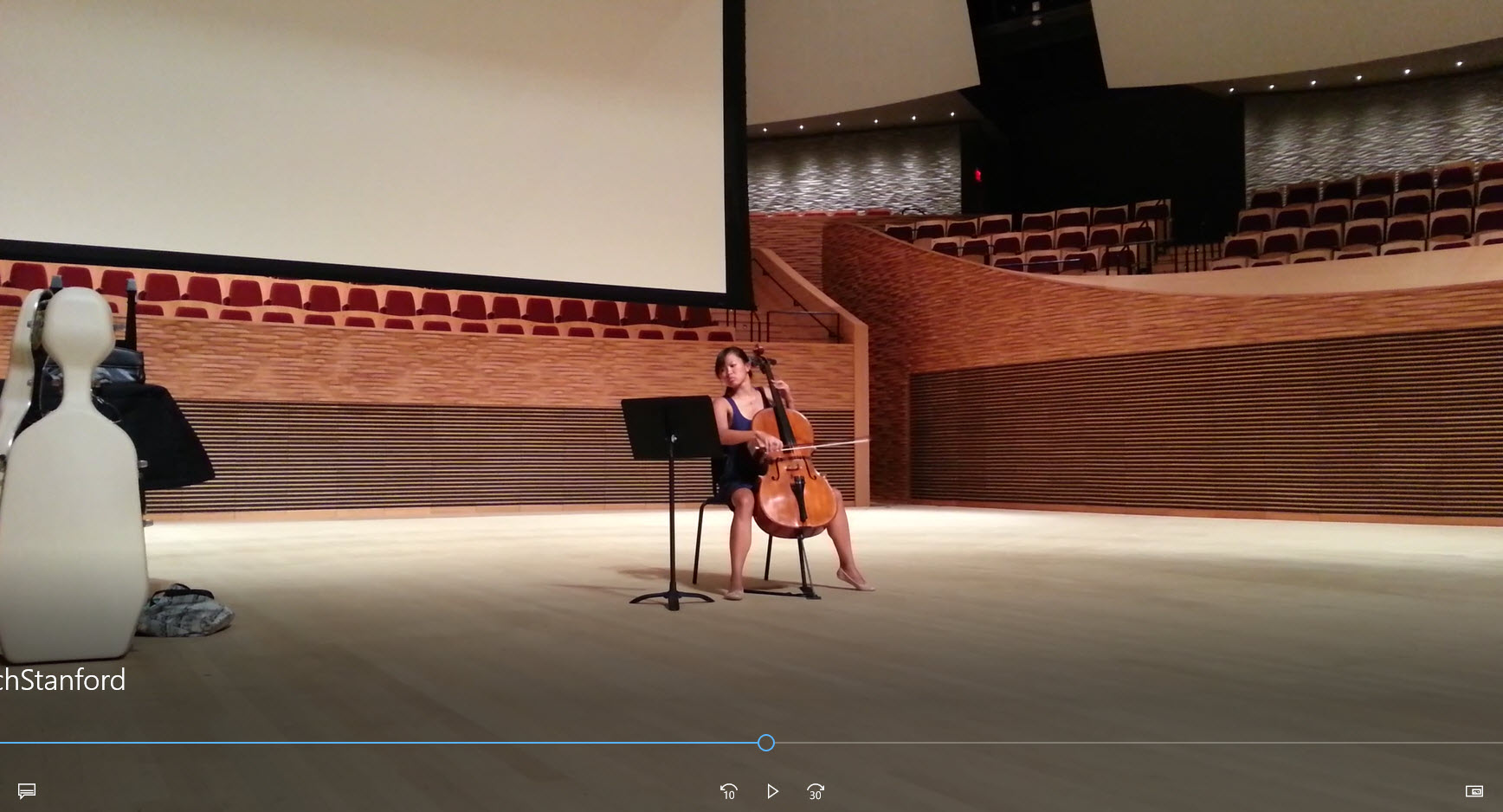

在大学最后一年的春天,女儿给我们送来一段录像,那是她的一场奇特的个人音乐会,地点在斯坦福的新音乐厅。偌大个现代化音乐厅,女儿只身在巨大的舞台上,

用德加尼表演巴赫的无伴奏大提琴组曲的G大调组曲,观众只有四,五个人。音乐厅音响一流,不用扩音设备,效果很好。表演虽无差池,看得出音乐处理不尽满意,琴的声音也大不如前。

后来才知道这场表演的缘由。女儿一位同学的父亲患了脑癌,他决定在有限的日子里做一些自己想做的事,参观和体验斯坦福大学是他想做的事之一。

这位同学希望女儿能在刚建成的新音乐厅为父亲作一次表演,女儿当然是赞成的。虽然近两年没有多少时间练琴,准备的时间也非常仓促,她还是尽量恢复了以前的曲目。

他们向学校租借了音乐厅的使用时间,于是有了这场演出。我知道后十分感动,这不正是音乐的功能所在吗?大提琴那令人深思的音色,巴赫音乐里对人生的悯怀,灵魂的娓娓对谈,

在这种场合最适合不过了。很少人知道,马友友的父亲临终时,友友在床前为他演奏的,正是巴赫的无伴奏大提琴组曲,c小调萨拉巴德(Sarabande),在2013年波士顿马拉松赛遇难者追思会上,

他也在广场上为大众演奏了这首乐曲。

德加尼琴在斯坦福的新音乐厅

为病人演奏巴赫组曲

时间飞快流逝。女儿医学院毕业,当了实习医生,她把德加尼又交到了我的手里,说:“我要去过三年的奴隶生活,再狠也抽不出时间来拉琴。”

德加尼躺在我面前,风姿依旧。琴身一尘不染,面板上1704配方的漆色锃亮,琴背那强劲的虎纹仍然炫目,女儿把它保养得很到位。试了几弓,却感到声音干涩,杂音丛生,反应迟钝,

在斯坦福音乐厅唱《乐可可主题变奏曲》那园润成熟的嗓音哪里去了?我虽有准备,知道它这些日子缺了关爱,心绪和体能都荒疏了,但没有想到如此不堪。女儿提醒我,

那次斯坦福音乐厅的演出是在她大学二年级那年,六年多了,她基本上没有怎么练过琴。是啊,六年多,落地的松子已长成大树,北极的冰川也融了多少,德加尼躺在琴盒里,不消沉也难。

我使出浑身解数想恢复德加尼往日的风彩。我把音柱重新调整,琴码重新细磨,换了新弦,改变音柱位置和琴码位置的各种不同组合,试了好几天,不见效果。我不相信这只琴会就此消沉下去,

因为我见过,每个人也都见过它辉煌的时候。我也知道德加尼不是品性易变得角色,需要有耐心和充分的时间。

我后来每天至少拉它一个小时,不管拉得好拉得坏,那是一种交流,一种关爱。几个月下来,它那圆润的声音又开始慢慢出现。像以前一样,晴天变阴时,你拉它D弦上的中音区,犹如品尝融化的蜂蜜。

那不是几块木板和胶水的拼合,不是像桌子椅子那样任人摆弄的木器,那是一个有灵的生命。

有一次,当代小提琴大师帕尔曼(Itzhak Perlman)接受采访时,记者问他,“你的琴值多少钱?”, 他看了记者一眼,又看看自己的琴,笑着一字一句地回答说,“相当贵(Very Expensive)!”

我知道,那不只是钱。

(2017年9月)

------------English Version ---------------

My Fate with Cello

It was my third flight with Balestrierius, from San Diego to Chicago.

Balestrierius is a cello. Like the most famous Stradivarius, Italian violins and cellos are usually named after their makers. Balestrierius’ maker, Thomas Balestrieri, was a violin maker

from Mantua, Italy. He was active in the Italian violin making industry from 1750 to 1780. He was the last master of the Cremona Violin Making School in Italy. He made more than 200 violins

and violas and nearly 50 cellos in his lifetime, which are scattered all over the world.

How did I get involved with precious violins? It all started with my daughter's cello lessons.

When my daughter was old enough to play a full-size cello, we ordered a Chinese cello for her. The maker of that cello was Mr. Wang from a violin shop in Shanghai. Mr. Wang is a graduate of

the violin making major at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. He is said to be a disciple of Tan Shuzhen, the former vice president of the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Tan Shuzhen is

a highly respected music educator, violinist, music instrument expert, and the pioneer of violin making in China. Mr. Wang's violin shop was doing very well at that time, and the teachers

we knew at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music also recommended buying cello from him. We ordered a cello for $2,500 and picked it up three months later. That was in 2001. After anxiously

waiting, I got the cello. I opened it and tried to play it immediately, I was disappointed. It was a mediocre piece of wood that just looked like a cello. The sound was like an unripe apple

that fell to the ground, no one would feel that it has a fruity taste.

My daughter's cello skills were improving, and she was constantly performing in competitions, which really made us anxious. If a violinist or cellist does not have a good instrument, he

will suffer a great loss in the competition. This reason is simple. In piano competitions, all contestants use the same piano, and the final comparison is about skill. In string instruments

competitions, everyone uses his own instrument, and the quality of the sound produced by the instrument is not only related to skill, but also the quality of the instrument and the judges

usually will not bother to distinguish between the two. Some people rent a good string instrument for their competitions, which is certainly a solution. However, it is difficult to master

a rented instrument in a short period of time, which is very disadvantageous to the performance in the competition. Long-term rental is too expensive, and a good violin of cello can cost

200 to 500 US dollars a day. We decided to buy a better cello for our daughter.

What is a good cello? When I was in junior high school, a good friend lent me a Guangzhou-made Bailing brand practice violin. It made me understand violins and even interested in music,

which benefited me for life. In my hometown in the southwest of China, the common good violins are Jinzhong and Zhenzhu brands made in Shanghai, and there are few foreign violins. Once,

there was a violin solo in the performance of the provincial song and dance troupe. The host introduced that the solo violin had a special experience. It was a violin in the private band

of warlord Ma Bufang, who was the king of the northwest of China. This violin was seized by the PLA during the war and the provincial cultural bureau spent 10,000 Chinese Yuan to buy it.

In that era, it was a very expensive instrument. At that time, I didn’t have a special feeling about the tone of the violin. I just knew that it was a German violin. From then on, I

believed that German violins were the best.

"Italian violins are the best," my daughter's cello teacher told us.

My daughter's teacher is a cello player with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra and lives in La Jolla.

"This is an Italian cello," she opened the case and showed us her instrument, "it cost me $250,000. You know, I bought this house in the 1970s for only about $250,000." La Jolla is an

upscale residential area in San Diego.

This teacher is just an ordinary member of the orchestra, while soloists have higher requirements for instruments. The situation of other members of the orchestra is roughly the same. For

example, another performer who graduated not long ago bought an Italian cello with a loan, which is worth $170,000. Of course, I also know that Yo-Yo Ma’s 1733 Italian cello Montagnana is worth

nearly $3 million. It is an Expensive profession, and of cause expensive hobby.

Later, when I had a more objective understanding of violin brands, I realized that a "good violin" is a relative standard for most people, determined by your ability and purpose. Tone

and ease of playing are the two most important indicators, and a violin that can meet these two indicators can come from any country and manufacturer. The reason why Italian handmade violins

from the 18th and 19th centuries have a high reputation is that they can perfectly meet these two indicators and other indicators for a long time. Of course, the market is very clear about the

price of those indicators. The higher the requirements, the higher the price.

I have no intention of spending a lot of money to buy a cello for my daughter. One reason is my financial constraints, and the other is that I am not sure to what extent my daughter's interest

will develop. Around $20,000 is probably within my price range.

"If you want to play a good cello but don't want to spend that much of money, then you will have to work hard on yourself." A good friend who knows string instruments teased me like this.

So you can imagine how I felt when I saw an Italian cello made in 1779 listed on eBay for $7,000. The seller was in Monterey, Northern California.

I flew to the charming bay city of Monterey, and rented a car and find the address. It was a rather luxurious seaside residence. I was greeted by a middle-aged Chinese woman who did not speak Chinese.

She immediately asked me to get in her car and took me to another place. In the car, she told me that the cello belonged to her father. Her father had just passed away and he had lived alone in an

apartment before, and now she was going there with me to see the cello. She also told me that her father was a cellist of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. He retired in the 1970s and came to the

United States to live with her family. Although the apartment had been cleaned, it still exuded the unique smell of a single old man. The space in the house was almost filled with vinyl records and

books and newspapers. A cello laid flat on the pile of books, without a bow, no bridge, and no strings, like a naked patient.

"This is it. My father never played it after he came to America. He gave away the case and bow, and only had this cello left. He wanted to keep it as a souvenir."

This is a weathered instrument. The wood is old, but the paint is still bright and shiny. There are a few cracks on the top, and the neck has been reattached. The label inside the violin

is old but still readable. It is printed in Italian with the name of the maker, Thomas Balesterieri, and the date of manufacture is 1779. In addition to the label, there is also a repair

label inside the violin. In 1899, the cello was repaired at James Hardie & Sons in Edinburgh, England, probably to repair the neck. It was time to test me. In such an environment where I

couldn't test the sound, what was the value of an old cello? I looked around the small house again. There was a musty smell in the dimness. The old man's diploma from St Mary’s Music School

in the UK had not been taken down in the frame on the wall. I felt that the aura of the old musician immersed in it could not be fake. I didn't believe that the violin he had used for decades

would be inferior to that Shanghai green apple. Coupled with my inexplicable admiration for Italian instruments, I decided to buy this violin. We closed the deal at $5,000.

Balestrierius celo trademark

So I took Balestrierius on an airplane for the first time.

As soon as I got home, I installed the bridge and strings and started to test the cello. As expected, it produced the deep and restrained sound of an old instrument, which is far better than

Mr. Wang's cello from Shanghai. The downside is that the sound is not loud enough. It is no problem for chamber music performances, but it may not be loud enough for performances in large

theaters. Anyway, I am quite satisfied. With this cello, the quality of my daughter's performances and competitions will probably be improved.

I started to research the history of this cello. According to online data, of the nearly fifty cellos made by Thomas Balestri, more than twenty have been registered by music stores around the

world and have certificates. The highest value of a Balestri cello with a certificate is about $500,000, and the lowest is nearly $200,000. So I had the idea of getting a certificate for this

cello.

Robert Cauer Violin in Los Angeles is probably one of the most authoritative violin shops in Southern California. The owner, Robert Cauer, has deep professional qualifications and skills,

and was once the chairman of the American Violin Makers Association. After understanding my requirements, Mr. Cauer brought out a large pile of reference materials, which was more than one meter

high from the ground, and flipped through them one by one. Finally, he told me his conclusion.

"I can't give you this certificate for two reasons. 1. The curling on the head of this cello is different from the curling made by Balestri. 2. The inlay on the edge of the cello is

made of different materials from the inlay made by Balestri." He showed me the relevant pictures and documents, which detailed the characteristics and style of Balestri's violin making

technology. I argued that the neck of this cello was repaired in 1899, and the head may have been changed. Mr. Cauer said that this possibility exists. But if the head has been changed,

it is difficult to define it as a Balestri cello, and there is no way to deny the problem of the inlay. I admire Mr. Cauer’s professionalism and professional knowledge. He spent more

than three hours with me that day and only charged me $50. Finally, he told me that if I want to further verify the authenticity of this cello, I can go to the Violin Academy in Cremona,

Italy, where there are more comprehensive and professional technologies. I know that well-known violin companies are very cautious in issuing certificates for famous instruments, especially

people like Mr. Cauer, who cannot leave any flaws in the industry.

Although I don't have a certificate, I'm willing to call this cello Balestrierius. The curling on the head aside, wouldn't Thomas Balestri have used other materials for the inlay? Of

course, I don't plan to go to Cremona to find out the truth at that time.

Balestrierius playing Saint-Saens

Cello Concerto No. 1 in church

My daughter won many competitions with this cello, and she performed many times in small venues such as churches and libraries, and the results were quite good. Later, she got an opportunity

to perform with the San Diego Symphony Orchestra at Copley Hall ( Copley Symphony Hall, San Diego), and finally she could test Balestrierius’ performance in a large theater with a big orchestra.

The cello concerto she played that day was Saint-Saens's First Cello Concerto. During the performance, I sat in the back of the theater, where the acoustics should be very good

because of the reflections. As a result, whenever the orchestra played louder, the cello's sound was suppressed and difficult to hear, making the concerto sound incomplete. As I had

intuition from the beginning, Balestrierius is a chamber music cello. I decided to get another cello with a stronger sound that can be played in a large theater and with a large orchestra.

The second time I took Balestrierius on a plane was to Onando, Florida, to look at a cello.

It was a high school teacher in O'Donnell who was in urgent need of money and wanted to sell his French cello. According to him, this cello had been performed in the Grand Theater with good results, and the attached

pictures were also pleasing to the eye. The high school teacher brought his cello and his girlfriend to the conference room of the hotel, holding a bottle of red wine in his hand, saying

that he wanted to celebrate the deal. He was an experienced performer, and he sat down and played Bach's D major suite on his cello. When I was fascinated by it, I asked him to play the same

piece again with Balestrierius. The results of the two were basically the same, and that was not the instrument I wanted. Despite this, the three of us drank red wine and said goodbye happily.

When buying a string instrument, it is a good idea to bring the one you are familiar with for comparison, which is a good method taught to me by my daughter's teacher.

This is the third time I am taking Balestrierius on a flight, because a student from the Chicago Conservatory of Music has an Italian violin made in 1890 to sell, and Balestrierius is

still my accompanying advisor.

The student originally majored in cello and bought this instrument in Italy for 11,000 euros. One year later, he decided to switch to conducting, so he wanted to sell it. This cello has a

fairly formal invoice from the violin store. The Italian trademark inside the violin says that the maker is Eugenio Degani and the production time is 1890. Eugenio Degani is the founder of

the modern Venice Violin Academy. He died in 1901. His violins are widely circulated in the world, and the price ranges from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars. I don't

care much about the orthodox origin of the instrument now. I want a loud and mellow sound that can be performed in a large concert hall. The sound volume of this cello is twice as loud as

that of Balestrierius, and the sound is a little worse, but I can see the reason. The quality of the bridge is not good enough, the strings are not the best, and the fingerboard is too low,

which makes the bridge too short and affects the vibration of the strings. I feel that these problems can be solved through my own efforts. I bought the cello on the spot for $5,000, plus a

good quality cello case. It was 10 o'clock in the evening when we finished the deal, and there were more than 7 hours before my return flight, so I took the two cellos and slept on a bench in

the Chicago airport hall with those homeless people.

Degany's trademark

When I got home, I was eager to show my achievements to my family. Suddenly, I saw that the head of Balestrierius cello case had been hit. I opened the case and saw that shock and anger

rushed from my spine to my head. My head exploded. The head of Balestrierius cello was completely broken off from the neck, like a person beheaded by a blunt knife. Only a few tendons

connected the head and body, those were the strings. I wanted to cry and scream. When I delivered it for shipment, I put labels all over the cello case saying "Fragile items, handle with care".

I didn't expect such bad airline service. It was another experienced cello teacher who told me that it is dangerous to save money on your instrument. When she travels, she never puts her

cello in the cargo hold for shipment. She has to buy a separate ticket for it. Fortunately, the newly bought Degany was fine. I think I must become a violin making expert now, otherwise

how can I deal with the maintenance and restoration of these two cellos?

I enrolled in an online course on violin making and repair at a music school in Chicago. The course uses a set of teaching materials by Henry Strobel, a contemporary American violin maker,

including all the technical details of violin woodworking, painting, debugging, and maintenance. As a practice of theoretical learning, I first repaired the headstock of Balestrierius.

The joy of success made me remake Degany without knowing the sky and the earth. I removed the fingerboard, raised it with mahogany, removed all the paint on the front panel, repainted

it, threw away the original bridge and strings, and replaced them with the world-recognized best French Despiau bridge, Danish Larsen and Austrian Spirocore strings. Later I learned that

it was probably because of luck that I didn't mess up. For example, painting a large area of a violin or cello is a very dangerous move, which is likely to cause the instrument to lose its

tone. I use the famous 1704 paint formula, which is said to have been created in 1704 and was passed down from the family Bible to the society by the descendants of the Italian Stradivari

family.

The result of my violin making skills training was tested in a more important competition that my daughter participated in three months later. My wife and I accompanied my daughter, and

she played Antonin Dvorak's First Cello Concerto on Degany. At the end of the competition, the judge shook my daughter's hand and said, "You played very well, the sound of the cello was

great, and the performance costume was beautiful!" The three of us all received the praise we deserved, and my wife was responsible for preparing the performance costumes.

Later, my daughter performed Degany in three public performances at the Torrance Cultural Arts Center in Los Angeles and the Conrad Prebys Music Center at the University of San Diego, all

with good results. After the two performances at the University of San Diego, someone told me that he could not tell much difference between the sound of my daughter’s cello and that of

Yo-Yo Ma. I know how much water there is in such words, but it is still very comforting as an encouragement and kind recognition. The performance at the University of San Diego was Dmitri

Shostakovich's First Cello Concerto. This is a piece of music that is recognized as very difficult by the music world. The contrast between the strong emotion of resistance and the pure

sadness and sorrow was not badly released by Degany in the concert hall, and was well received by the conductor and the audience.

Degany performs Shostakovich's

Cello Concerto No. 1 in San Diego

After my daughter went to college, I once called her in Northern California, and she casually said that she had a performance over the weekend.

"What show?"

"Play Rococo with the university symphony orchestra."

"Why didn't you tell us earlier? We are going to drive over here to listen!"

My daughter won a music competition at school and will perform Tchaikovsky's cello concerto "Variations on a Theme of Rococo". When my wife and I sat in Stanford Music Hall waiting for the

concert to start, it was only 20 hours since we learned about the concert. Although the performance of the concerto's orchestra was not satisfactory, my daughter played quite well. She played

the cello at her best, even better than in San Diego. Degany sometimes sang Tchaikovsky's incomparable beautiful melody, and sometimes simulated passionate emotions, with both tenderness and

power, and the sound of the cello that the orchestra could not suppress echoed in every corner of the hall.

After the concert, I praised my daughter and said:

"This is probably the pinnacle of your performance and the best performance of your cello!"

"Is it going downhill for me and my cello?" she asked me jokingly, and then continued, "I am really familiar with this piece of music. It is not difficult. I feel more mature as I get older.

You mentioned the cello’s timbre. It may be because the effect of this concert hall is so good."She is always that humble.

I know that the real reason why she and her cello performed so well in the concert was partly because she took the chamber music theory and practice course in the music department in her

freshman and sophomore years and spent a lot of time with Degany. In my experience, this is unsustainable. In the future, a large number of heavy courses, studies and life plans will take up

a lot of time, and at that time, interests and hobbies will naturally be put on the back burner. I didn't say it out loud.

In the spring of her last year at university, my daughter sent us a video of a unique solo concert of hers, which took place at the new concert hall at Stanford. In such a large modern

concert hall, my daughter was alone on the huge stage, playing the G major suite of Bach's unaccompanied cello suite with Degany, there were only four or five people in the audience. The

acoustics of the concert hall were first-rate, and the effect was very good without the need for amplification equipment. Although the performance was flawless, it was obvious that the

music processing was not satisfactory, and the sound of the cello was not as good as before. Later I learned the reason for this performance. The father of one of my daughter's classmates

had brain cancer, and he decided to do something he wanted to do in his limited days. Visiting and experiencing Stanford University was one of the things he wanted to do. This classmate

hoped that my daughter could perform for her father in the newly built new concert hall, and my daughter certainly agreed. Although she had not had much time to practice the cello in the

past two years and the preparation time was very rushed, she still tried her best to restore the previous repertoire. They rented the concert hall from the school for use, so this

performance took place. I was very moved when I learned about it. Isn't this the function of music? The thoughtful timbre of the cello, the compassion for life and the soul-talking in

Bach's music are most suitable for this occasion. Few people know that when Yo-Yo Ma's father was dying, he played Bach's unaccompanied cello suite Sarabande in C minor for his father at

the bedside. He also played this piece of music for the public in the square at the memorial service for the victims of the Boston Marathon in 2013.

Degany plays Bach suites for patients

in Stanford's new concert hall

Time passed quickly. My daughter graduated from medical school and became an intern. She handed Degany back to me and said, "I'm going to live a slave life for three years. No matter how

hard it is, I won't have time to play the cello."

Degany lay in front of me, still graceful. The body of the instrument was spotless, the 1704 formula paint on the panel was shiny, and the strong tiger stripes on the back of the instrument

were still dazzling. My daughter took good care of it. I tried a few bows, but the sound was dry, full of noise, and slow to respond. Where was the mellow and mature voice that sang "Variations

on a Theme of Rococo" at Stanford Concert Hall? Although I was prepared, I knew that it had lacked care these days and its mood and physical strength were neglected, but I didn't expect it to be

so bad. My daughter reminded me that the performance at Stanford Concert Hall was when she was a sophomore in college. It has been more than six years, and she has basically not practiced the

cello. Yes, in more than six years, the fallen pine nuts have grown into big trees, and the glaciers in the Arctic have melted a lot. It is hard for Degany to not be depressed lying in the

cello case.

I tried everything to restore the Degany to its former glory. I readjusted the sound post, re-grinded the bridge, replaced new strings, and changed the sound post and bridge positions in various

combinations. I tried for several days, but to no avail. I didn't believe that this instrument would be depressed, because I had seen it, and everyone had seen it in its glory days. I also knew

that Degany was not a character that could be easily changed. I needed patience and sufficient time.

I played it for at least an hour every day, no matter how good or bad it was, it was a kind of communication, a kind of care. After a few months, its mellow sound began to slowly appear again.

Just like before, when the sunny day turned cloudy, you played the middle range on the D string, just like tasting melted honey.

It is not a few pieces of wood put together with glue, nor is it a wooden object that can be manipulated at will like a table or chair. It is a living being with a soul.

Once, when the contemporary violin master Itzhak Perlman was being interviewed, the reporter asked him, "How much is your violin worth?" He looked at the reporter, then at his violin, and

smiled and answered word by word, "Very Expensive!"

I know, it's not just about money.

(September 2017)